Antes de la llegada de los españoles, las tribus aborígenes de Sudamérica conocían la milagrosa propiedad de la corteza de un árbol que aliviaba la fiebre y el dolor, así que cuando los europeos trajeron el paludismo (o malaria) los nativos decidieron usar aquel viejo remedio para este nuevo mal. El asunto es que los españoles no habían tomado muy en serio esta medicina ancestral, hasta que en 1632 la esposa del Virrey de Perú, la Condesa de Chinchón, cayó enferma de malaria. Al borde de morir y en medio de una delirante agonía un sirviente sugirió que la trataran con la corteza del árbol milagroso y para sorpresa de todos se recuperó.

La Cinchona or Quina, the miraculous tree

En 1935, el jesuita Bernabé Cobo, ya documentaba sus milagrosas propiedades: "In the terms of the city of Loja, diocese of Quito, a certain breed of large trees is born that have the bark like cinnamon, a little thicker, and very bitter, which, ground into powder, is given to those who have fever and with only that remedy they are removed ”.

From there they named the miraculous tree in honor of the woman and named it Cinchona. Its bark traveled to Europe and its popularity only grew. They took it by the ton, in ships laden with bark and precious metals. They called the bark Quina and later the first European chemists extracted its active element from it and called it quinine.

Legions of intrepid adventurers scoured the South American jungles in search of new varieties of the Cinchona tree in hopes of finding more effective barks. And they found them! They questioned the aborigines and they told them about the Quina Amarilla tree, the Quina Colorada and even the rare Quina Canela tree. There are many chronicles of these adventurous scientists who were in charge of writing in their diaries their adventures in the middle of the jungle looking for the Cinchona. They are worth reading, as I guarantee that they are up to any Indiana Jones movie.

Una de estas historias de aventura es la de Charles Marie de La Condamine, científico francés que vino a Ecuador en el siglo XVIII a demostrar que la tierra es achatada en los polos y así comprobar que las afirmaciones del afamado Sir Isaac Newton eran ciertas. En ese entonces Ecuador ni se llamaba así y medir no era una cosa de encender un GPS y ya. Casi 10 años le tomó la bendita medición y como es de suponer, tuvo tiempo suficiente para satisfacer su curiosidad científica en otros aspectos. Cualquier cosa con la que La Condamine se tropezó llamó su atención y la documentó. En sus exploraciones encontró una especie de árbol de Cinchona muy efectiva y comunicó esta información a la comunidad científica francesa, quienes propagaron este descubrimiento en todas las direcciones y pronto comenzaron a importar esta variedad de corteza desde el Nuevo Mundo.

As it was a good business to export the bark to Europe, the South American countries put customs restrictions so that the seeds of Cinchona cannot leave their lands and thus prevent this little tree from being planted on other continents and monopolizing its trade. But this did not last long, soon English merchants managed to convince an indigenous man named Manuel Incra to get a batch of seeds that they took to London and later sold to the Dutch at the price of gold. The story goes that the Dutch decided to take them to one of their colonies; more precisely to the island of Java, now part of Indonesia. Henceforth the Dutch supplied much of the world's demand for quinine.

Carbonated water, the invention of sensation in Europe

While quinine was causing a sensation as a medicine in Europe, a Geneva watchmaker named Johann Jacob Schweppe had managed to put carbon dioxide into the water, giving rise to the now popular carbonated waters or fizzy drinks. He founded a company and created various fruit-flavored drinks. By the second half of the 19th century, there were already several soft drink factories in England, experimenting with fruit and plant flavors. Soda drinks with healing properties could not be absent and eventually someone came up with the idea of adding quinine to carbonated water. It can be said that the invention of carbonated water and the discovery of quinine coincided in time and it was only a matter of finding a suitable head to conceive the idea.

The carbonated water with quinine was baptized with the name of Tonic water And the watchmaker Schweppe also jumped on the fashion train and brought out his own version of tonic water, which still lives on to this day under one of the best-known brands in the world: Schweppe Tonic Water.

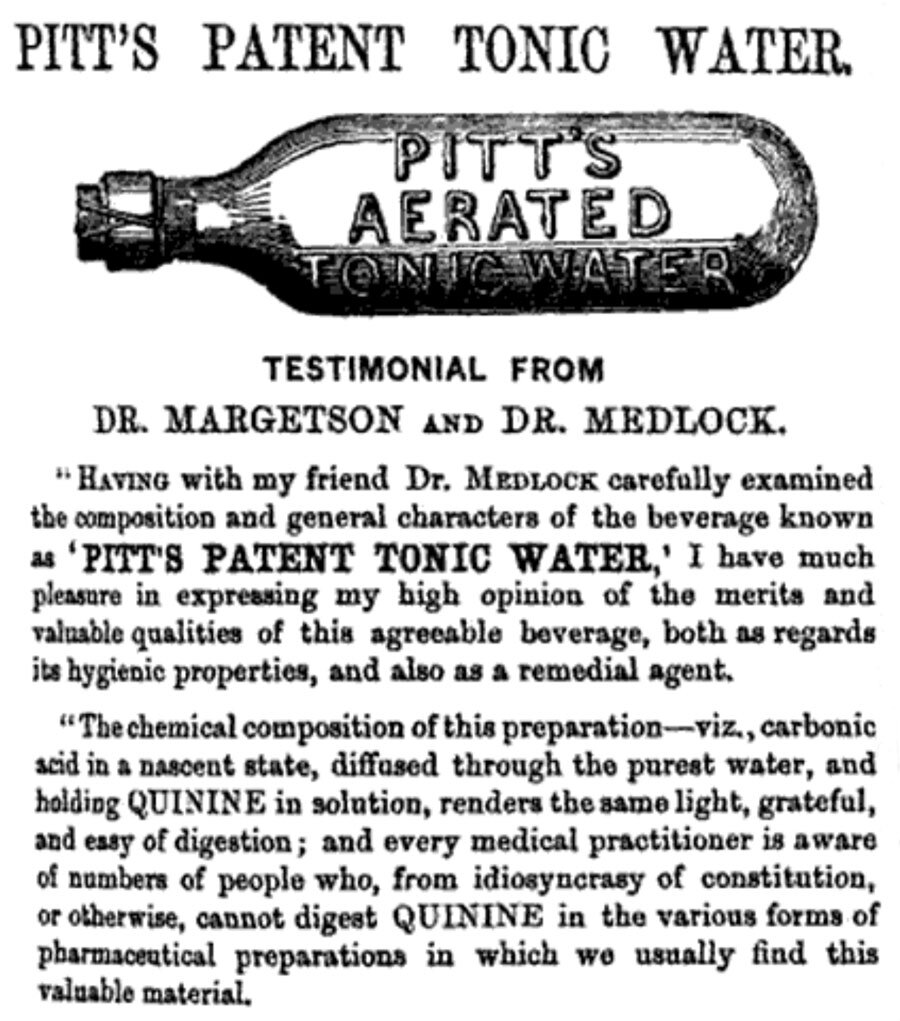

Schweppe was not the only one, several other manufacturers did the same and thus brands such as Cunnington's tonic water or Pitt's tonic water were born. They all touted the apparent health benefits of their products. The following is an advertisement that appeared in a London publication from 1861, describing the benefits of Pitt's tonic water.

Other interesting carbonated drinks also emerged, such as gingerade, which is nothing more than the well-known Ginger Ale of our times. That is, a drink based on ginger and carbonated water.

It happened one fine day that the English army that was stationed in India (then an English colony) was provided with a good dose of tonic water. The English had the wrong theory that tonic water not only relieved malaria but could also prevent it, so they decided to supply the army with this drink. What they did not calculate was that the tonic water tasted like a \ ”remedy \” (in fact it was), since it was much more bitter then than it is today.

This caused the soldiers to not want to take it until someone had the fantastic idea of adding a little Gin to it. The rest of the story already know it 😉