Today we all assume as an indisputable truth that Alexander Graham Bell is the inventor of the telephoneBut in the mid-nineteenth century, when this artifact did not yet exist, there was an unusual movement around this possible invention that many already envisioned as the “talking telegraph”. This caused several enthusiasts to work on the same idea simultaneously, which eventually turned into a marathon race to see who made it to the patent office first. What you will read next is an important, but often unknown, part of the history of telephony.

What you will read next is based on the first chapter of a book that I published a few years ago and that I thought it appropriate to share. In it you will notice the hectic development of events that ended in what we call today telephone and also one of the greatest controversies regarding patents of all time, so important that the Congress of the United States of America ruled on the matter more than a century later.

Antonio Meucci and his experiments in Havana

The year 1849 passed in Havana, at that time still a Spanish colony. Antonio Meucci, an Italian chemist and doctor, had moved there with his wife in search of work in one of the most important theaters on the continent, the Tacón Theater. He had been tasked with building a water purification system for the theater.

He worked on his designs in an office that he had set up on the ground floor of his own house and from time to time he would go up to his bedroom to check the health of his wife, who suffered from pain due to rheumatism. I suppose that like any inventor, he saw in this discomfort an opportunity to solve a problem and had the idea of building a device to be able to communicate with his wife without having to go up to the bedroom. He installed a cable from his office to his room and after a few unsuccessful attempts he managed to hear his wife's voice coming from a rudimentary diaphragm. The invention was a surprise to his neighbors and the population in general, but in Cuba at that time there was no important scientific community that echoed his invention and after a few years, he decided to move to the USA. Thus it was that in 1854, the same Meucci, already with his perfected device and with several diagrams drawn by himself, made a new demonstration of his invention in New York City.

The telephone ideas of Charles Bourseul

But while Meucci managed to perfect his phone, on the other side of the world, in France, a story no less interesting was being woven. A modest worker at the telegraph company was making improvements to the telegraph network and came up with a method to convert voice into electricity. In fact, it can be said that it was a precursor of what we know today as a microphone. The name of this skilled French engineer was Charles Bourseul.

Bourseul's curiosity did not stop there, he also imagined a telephone system with all its components and even took care to write his idea and send it to a well-known Parisian magazine of the time, called L'Illustration. The directors of the magazine did not hesitate to publish their writings. The curious thing about all this is that the publication took place almost simultaneously with the Meucci demonstration in New York, in 1854.

Bourseul's only problem is that he took care to build a working prototype of his voice transmitter device, but he never carried out the full experiment and as far as we know, he never finished building the missing part: the receiver or speaker. Construction apparently began, but after a few failed attempts, he lost interest in finishing it. The only thing that remains for sure as proof of his adventure is the copy of that Parisian magazine.

Johann Philipp Reis and his phone prototypes

There must have been some sort of alignment of the planets that year, since it seems that a copy of that magazine fell into the best possible hands. Those of the brilliant and meticulous German engineer Johann Philipp Reis.

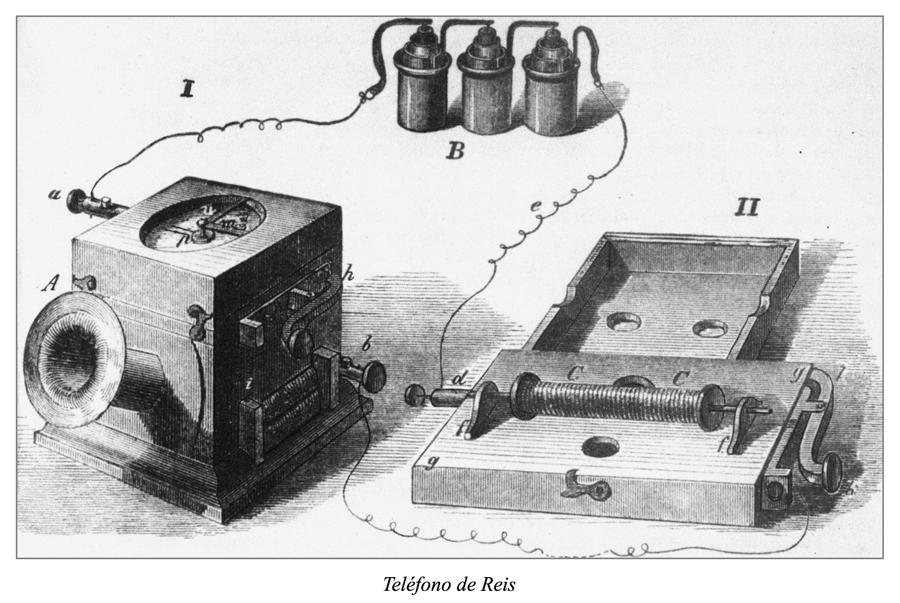

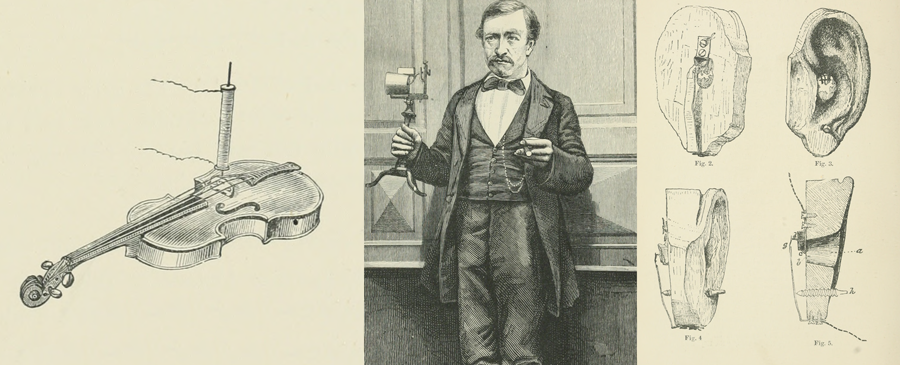

Reis was working as a physics teacher at the time and the idea immediately captured him. He decided to continue with Brouseul's idea and build a whole series of prototypes in the most neat and obsessive way imaginable. At first he did it in a rudimentary way, working in a makeshift laboratory in his backyard and making clever and creative use of common materials. He used cork, a knitting needle and even the "skin" of a sausage as the membrane for his transmitting apparatus. He carved a set of human ears in wood, to understand how it captured sound waves and thus be able to emulate their behavior. He made several versions of all the components to find the best alternative for each one. He documented the entire process in a very patient way and thanks to that today we have a whole series of beautiful illustrations of his work.

To build the unfinished component of Brouseul, he had an ingenious idea, visited his friend Professor Peter, a music teacher, and borrowed his violin. Peter not only loaned it to him but gave him a violin that he did not use. He made a kind of electromagnet brush his strings and after a few tries, he managed to get sounds out of the instrument. The violin itself has a resonant acoustic chamber and it was able to amplify the sounds in such a way that something very similar to the voice was heard.

But this was only the beginning, in a short time he would replace the violin with a resonating box built by himself and then he would further improve the receiving device by making it more compact. This whole process took several years and this is how it was in 1860 Reis He finishes perfecting his telephone set and documents his achievement very well. It should be noted that it was Reis himself who decided to give the name "telephone" to his newborn child, thus coining the term. To put things in perspective, at the time Reis finished his invention, Graham Bell was a 13-year-old boy.

The rejection and acceptance of Reis's new ideas

The following months were frustrating. Reis notified several scientific journals and gazettes of his invention, obtaining only rejection or incredulous responses that underestimated the importance of his invention. In 1862 he sent an article to the German magazine Annalen, and its editor, Professor Poggendorff, refused to publish the article on the grounds that it was scientifically impossible to create such a thing. It was only in 1864 that Reis decided to gamble and make a live demonstration to the most renowned German scientists. The positive response was immediate, even Poggendorff himself offered to publish his article, in order to repair the previous mistake, but Reis, now swollen with pride, objected.

Johann Philipp Reis spent the next two years trying to impress the German public, as he had penetrated the scientific sphere but even his invention was not known to the masses. Unfortunately time was not enough for him and he soon fell ill and had to slow down. He could only continue with his work as a teacher, alternating his time with sporadic appearances before the scientific community. It is said that he installed a telephone line to the classroom where he taught and the students tried not to say inappropriate things in his absence for fear that they were being heard through Professor Reis's telephone. He died in 1874, just under 10 years after his demonstration to the German scientific elite and just a year before Graham Bell's patent, after which his achievements were practically forgotten.

Now let's take a brief parenthesis here to ask ourselves a question. Do you think that by now there are enough actors involved? Well, what can I tell you, there is still much more "fabric to cut" although it seems incredible.

Innocenzo Manzetti, another Italian in the race

It happens that in Italy there was also an interest in the long-awaited “talking telegraph”. Even before Meucci, an inventor named Innocenzo Manzetti imagined the artifact as early as 1843 but didn't decide to build it until 1864.

Manzetti was working on several inventions at the same time, so the telephone was just another one and he probably did not give it all the importance it should have. In fact, he was obsessed with building a kind of robot automaton that played the flute. As far-fetched as it may seem by the mid-nineteenth century, it turns out that Manzetti had a more or less functional prototype of his humanoid. So impressive was his automaton, that to give us an idea he could perform more than 10 opera arias. Surely the telephone seemed like a second-order invention at first and it only gave you the interest it deserved when it occurred to you that your automaton could not only play the flute but also talk! Yes, the telephone was for Manzetti just an accessory to his automaton.

For the happiness of the most curious, the cybernetic flute-playing automaton remains practically intact to this day and is the main attraction of the Manzetti Museum, located in Aosta, the small town where Manzetti was born, in northern Italy. I leave you a link in case one day you decide to go for a walk http://www.manzetti.eu/il-museo/.

It is also important that we realize that Manzetti built his telephone in 1864, the same year that Reis was showing his invention to the German scientific community. More coincidences.

Since the telephone was only an accessory to his automaton, Manzetti did not immediately advertise it until a year later, when he realized its application by transmitting voice over telegraph cables. It was only in late 1865 that a French magazine called Le Petit Journal decides to publish a review in its section CURIOSITIES OF SCIENCE. Luckily for the most curious readers I have a copy of this historical copy and can download it from the following link.

Many rumored that several technicians from the English telegraph company became interested in Manzetti's invention, went to visit him in Italy and returned to London with inside information that later reached the ears of Bell and so it was that the latter learned the details of the "gold mine" that he later patented; but everything remains in the field of speculation. What does seem certain is that really English technicians came to visit him, as there is a record of this episode in the newspaper La Feuille d'Aoste in August 1865.

The problem with telephone patents

So far at least something is obvious, the invention of the telephone was being worked on simultaneously and without respite in several countries, independently. The knowledge and technology of the time had pointed all their spears in the same direction and many saw it almost at the same time, as if by magic. Humanity was ready for the invention, it cried out for it, it needed it. The revolution in human communication was yet to come, it was only a matter of time, just as it happens with other human inventions.

The truth is that in this world we can all have ideas, we can all build prototypes, but unfortunately the economic profit takes it; not whoever has the idea first, nor who makes it first, but who patents it first. Unfair? I do not know, but it is the subject of another article surely. The reader, after reading this story, will be able to judge whether or not these tireless predecessors have any merit, who burned their eyelashes and paved the way for what we know today as the telephone. In any case, the reader should also know that there is still another very important actor in this story and it is not exactly Bell, as we will see later.

Actually, to be objective, the first to try to patent the invention was Meucci, of whom we spoke at the beginning of this story, who in 1871 signed a document of "patent notice" but due to his economic condition he could never pay the money for complete this process and your document expired a few years later.

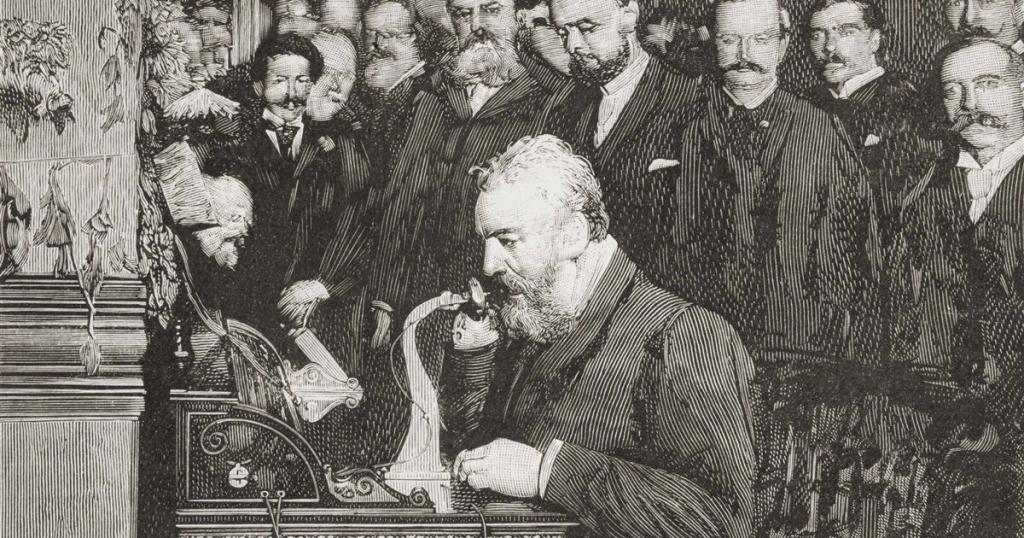

In 1875, a year after the Meucci patent process expired, Alexander Graham Bell, a Scotsman living in the United States, succeeded in patenting the long-awaited telephone and was the first to complete the patent process.

The truth is that Bell had previously been experimenting with some ideas to conceive his telephone device until one day he managed to pluck some sounds from the electricity. The story goes that the first call he made was to tell his assistant the famous phrases "Mr. Watson, eat here. I want to see you. " ("Mr. Watson, come on. I need to see you.").

One more character, Elisha Gray

But the history does not finish here. Perhaps the character who sparked the most controversy with the invention of the telephone was not any of those of us who have spoken so far, but Elisha Gray.

What makes Elisha Gray's case particularly important is not that she also built a phone like several others, but that it unbelievably made it to the patent office just hours after Bell. Imagine, humanity spent thousands of years accumulating knowledge, studying the nature of sound, discovering electricity, inventing the telegraph, forging everything necessary to give shape and time to an artifact ... and it turns out that two people coincide in the SAME patent office to patent the SAME thing only hours apart. Really amazing and for some: impossible.

The two inventors got into a well-known legal dispute that Bell eventually won after a long battle. This dispute was so complex and lengthy that it is in itself an interesting case study and an entertaining story at the same time. The coincidences between the two patent applications are so amazing that they have given rise to the most fantastic conspiracy stories. If anyone is interested in knowing more details, I share the Wikipedia link and I recommend preparing a good coffee https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisha_Gray_and_Alexander_Bell_telephone_controversy

Western Union rejects the idea of the telephone as a toy

At the end of the day, thanks to the patent, Bell was able to turn the idea of the telephone into a profitable business and he has the credit of having developed the idea and turned it into something practical for society. Bell became one of the richest men in the world. It is said that at one point Bell tried to sell his patent to Western Union for $100 thousand dollars but the president of Western Union refused because he considered that the phone was nothing more than a toy. Just two years later, the same Western Union manager told his colleagues that if he could get Bell's patent for $ $25 million, he would consider it a bargain!

So who invented the telephone?

Regardless of who obtained the right to commercialize the invention and took the fame, what can be said is that if Meucci had had the $10 to pay the patent, surely the credit would have been taken by him.

So far my desire to make known the other part of the events that occurred practically in parallel to the famous Bell patent, the rest of the story is already known to all of us.