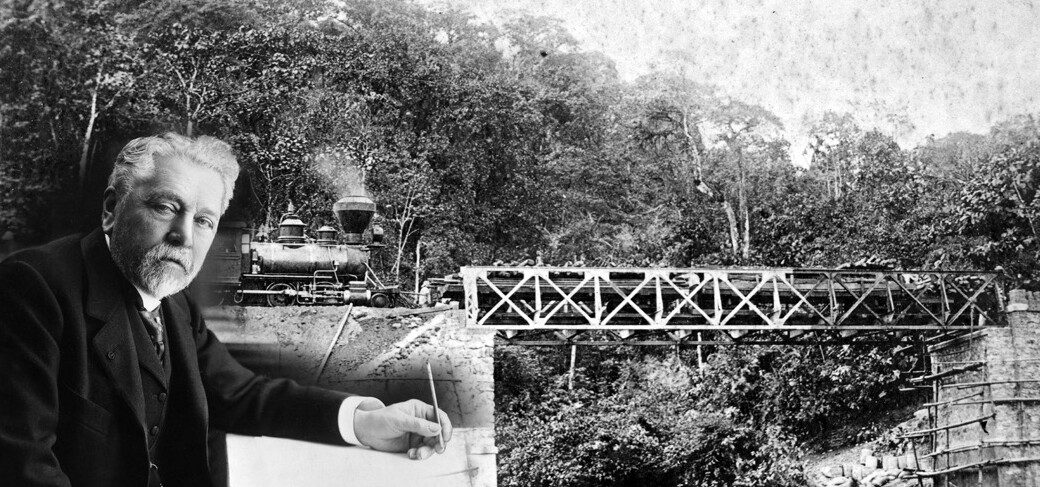

A few months ago (2013), reading a book on the history of Ecuadorian railway, I came across a paragraph where a supposed bridge over the Chimbo River built by Eiffel was mentioned.

I was struck by not having heard before about this. Would it be true? Eiffel is quite a character and Eiffel's works tend to be attractive all over the world. How could it be that the existence of this bridge is not common knowledge?

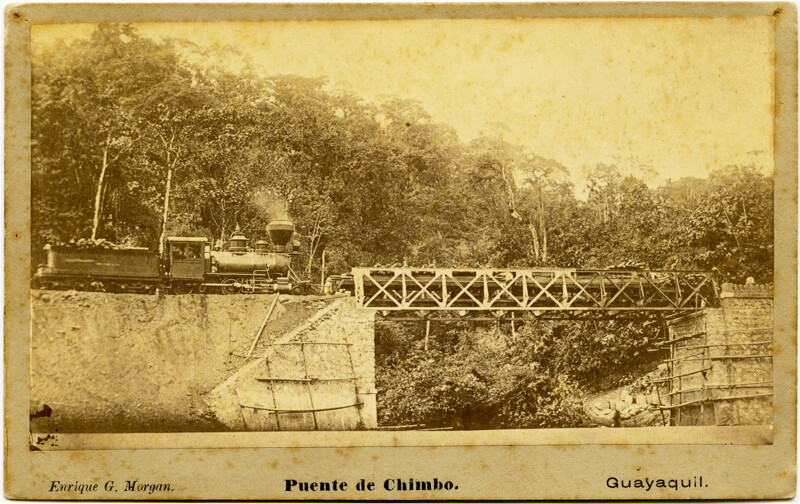

Curiosity led me to investigate further. After a while I was able to get two photos of the aforementioned bridge and the year of its installation: 1886.

The first thing that stands out is that it was a simple bridge. I was expecting a monumental arch bridge or something like that. Eiffel had built some large arch bridges that had made him a renown at the time as a designer of metal structures, such as the Garabit Viaduct or the bridge Maria Pia. However, when looking at the photos of the Chimbo bridge, it is evident that it was a low “light” bridge, which made an arch bridge unnecessary; it would have been a waste of resources. Eiffel did the right thing.

But, despite the simplicity of the structure, at the end of the day it was still an Eiffel bridge! ... curiosity increased ... Many unanswered questions haunted my head: will the bridge still exist? In what conditions? Is it buried in the undergrowth? Will it be used yet?

There was only one way to solve this mystery… it had to be found!

The next thing was to determine its location. In old books it is mentioned that the bridge was very close to the town of Chimbo, so for several weeks I was confused. The only Chimbo population that appears on current maps is San José de Chimbo in the Bolívar province and there were no traces of the railroad there, worse from the bridge.

So where was that Chimbo? Where was the happy bridge?

Some history

Here I am going to make a parenthesis, to briefly tell a passage in the history of the Ecuadorian railroad that will allow us to clarify the situation a little more.

It turns out that in 1886 (the date of the bridge's installation), the plan for laying the southern railway line was different from the one that was finally concluded at the time of Eloy Alfaro (in 1908).

García Moreno had successfully built the Yaguachi-Chimbo line and in 1885 President Plácido Caamaño hired the English engineer Marcus J. Kelly to continue the work, from Chimbo to the mountain town of Sibambe.

Kelly proposed to Caamaño to create 82 kilometers of road and build administrative offices in both Chimbo and Sibambe.

In fact, it was Kelly himself who brought and installed the bridge, as researcher Karl Dieter Gartelmann tells us in his book NOSE OF THE DEVIL AND THE BLACK MONSTER.

In Paris, Kelly had had the opportunity to visit the workshops of the engineer Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel, who was widely known in Europe as a builder of metal bridges. Kelly commissioned him to build a new bridge over the Chimbo River, which was installed in 1886.

As an interesting fact, and to add more spice to the matter, it should be noted that in 1886 Eiffel's magnum opus had not yet been erected: the famous Eiffel Tower.

Did the town of Chimbo exist?

With what has been read so far, one already gets the idea that Chimbo should have been an important place. The railway line reached there (it was the last station), which apparently made it a key place, where the railroad merchandise was shipped on mule back to be transported to Quito. Also, Kelly planned to make administrative offices there.

But this idea of an important Chimbo totally contrasts with reality ... Chimbo, it does not exist in current maps.

The mystery becomes even more interesting when one reads what the scientist and adventurer Edward Whymper wrote in the memoirs of his travels through the Ecuadorian Andes around 1880 (that is, 6 years before the installation of the supposed Eiffel Bridge).

The Chimbo Bridge, a wooden construction, crossed the river of the same name before it turned sharply to the west. the road was hidden among weeds, and had to be discovered; But we did not find a station or trains, a house, a cabin, or people or means of obtaining information. The right bank of the river formed the end of the road that reached the edge of the stream, without obstacles that would prevent the fall of a train into the waters ...

Several things are evident here. First, Whymper ran into the end of the road, where the town of Chimbo was supposedly located; the second, it gives us a location reference when it says "Before it (the Chimbo river) turned sharply to the west"; and third Chimbo did not exist as a town at that time (1880). There wasn't even a station or people in that place, just the metal of the rails.

However, Whymper later recounted that a train did indeed arrive at that abandoned place, and that it transported it to Yaguachi. That is to say, in effect Whymper was in the place where the town of Chimbo should be born later.

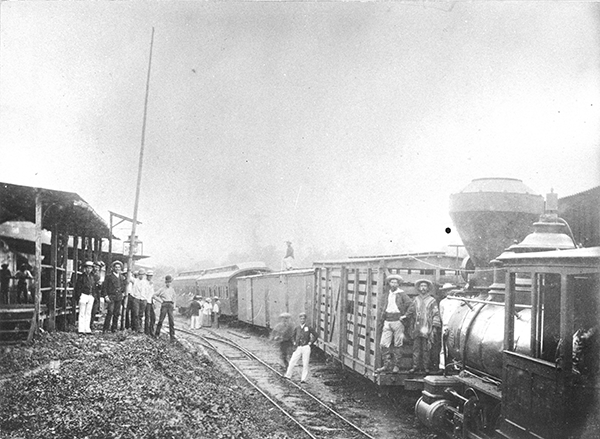

At some point in history, Chimbo grew in importance, that is clear. What's more, during the investigation I was able to find two photos of Chimbo. These do not reveal much information about the importance of the town, but at least it can be concluded that it was an established hamlet. I mean, it existed!

This hypothesis is reinforced by the writer Galo García Idrovo, when he writes in his work The Most Difficult Railway in the World:

With the passing of time, this entire sector gradually became inhabited by immigrants from other sectors of the Bolívar province and the Sibambe parish, until it formed a small population that just took the name “El Chimbo”.

Looking for traces of Chimbo's location

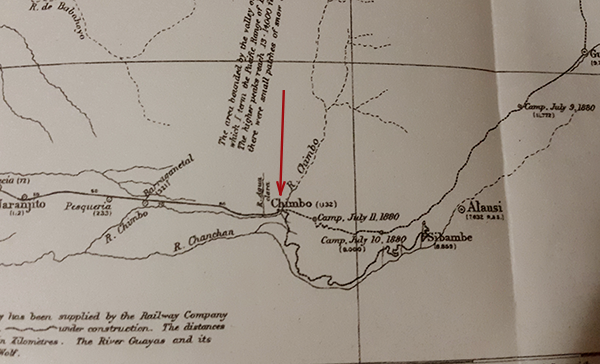

The first clues to Chimbo's approximate location appeared by simple logic. It had to be next to the Chimbo River and, as Whymper had written it, where the river turns sharply to the west. Also, it was the end of the railroad line.

Analyzing these two clues, it is obvious that Chimbo should be close to the current town of Bucay.

This is consistent with the testimony of Don Daniel Barragán in Galo García's book:

… Managing to reach the sector called “del Chimbo”, a site located a few kilometers north of Bucay and which takes this name precisely because it is located next to the Chimbo river.

However, the exact location would come from an old map drawn up by Whymper himself.

Whymper was an avid observer, a good draftsman, and a lover of detail. He took the time to draw up a map of the route he traveled, based on his own measurements and on certain references from the La Condamine and Pedro Vicente Maldonado maps, which existed until then. Whymper did not rely on them entirely, discovering inaccuracies.

Thanks to this prolix documentary by Whymper, the location of Chimbo was fully revealed.

We put on our boots and went looking for the bridge

At this point I had already infected my good friends Vicente Adum (Chento) and Paul Estrella with curiosity; and had convinced them to go find the bridge. The chosen day was Saturday January 10th of the present.

Chento is a fan of the history of railways and locomotives just like me and Paul, as a photography fan, he accompanied us on the adventure equipped with his camera.

The first stop on the trip was Bucay. We did not get much information about the bridge here, except for the testimony of Don Eduardo Benavides, ex-machinist, who mentioned that our bridge could be one near the village called La Victoria, on the road to Pallatanga. We are heading in that direction.

The Eiffel Bridge appears

We stopped at the entrance to La Victoria and tried to find a way to get to the river. Plan A was to walk along the bank of the Chimbo, at some point we would have to run into the bridge or its bases.

The thick vegetation made the task a bit difficult, so we decided to look for an alternative route, when suddenly Chento shouted: "here it is, here is the bridge!"

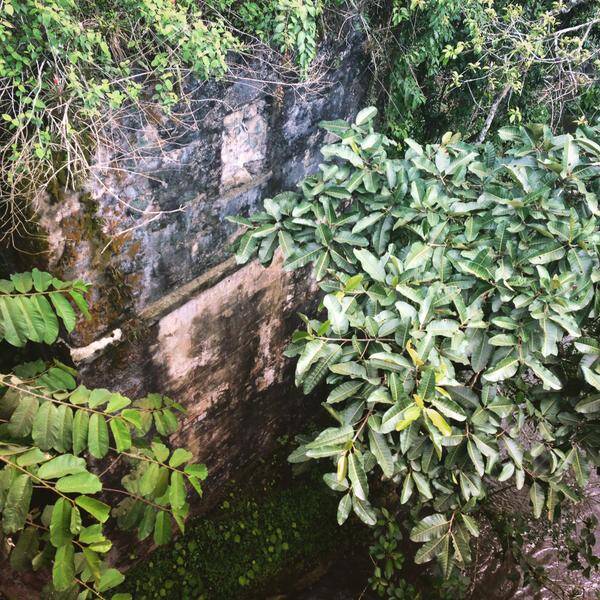

It turns out that the elusive Chimbo Bridge, or what was left of it, was located just below the current vehicular bridge that passed over the Chimbo River. Somewhat covered in vegetation, but visible. It was on our noses the whole time!

The bad news is that nothing remains of the metal structure that was once built in the Eiffel workshops. However, the foundations are almost intact, as in their best days.

We rushed to look for some unique marks on the bridge, which we were finding without much difficulty. One of them was a rectangular window-shaped detail on one of the main columns; another was a horizontal edge that divided the masonry ... In a few minutes it was obvious to us that it was the same bridge: the historic Chimbo bridge.

In the previous photo you can see the eastern base, built of stone. You can distinguish the difference in color between rectangular masonry (bottom) and irregular plastered stone (top). Between them there is a horizontal curb and on the plastered stone a rectangular detail of a slightly different color.

The mixture of emotions was intense. We felt like legendary expeditionaries. The joy of the discovery competed with the sadness of not having already found anything of the metallic structure that one day rested on these bases. It was also like transporting us to the distant 19th century and imagining the days when this work was built on the Chimbo ravine, without the advantage of current machinery and instruments; We were amazed at how the construction was still almost intact.

The fate of the bridge

On the way back to Guayaquil and with the satisfaction of having found our loot, we wondered what the fate of Eiffel's metallic structure had been. Would it have been reused on another bridge? Had it been stolen? Would they have melted it?

Everything was speculation until that moment, until a day later, still excited and devouring a couple of books on the history of the railroad, I came across a report, from the Guayaquil & Quito Railway Company, written by John Harman, towards the Minister of Public Works of that time. The report is dated July 1900 and would seem to suggest what we least imagined - the saddest outcome of a bridge built by Eiffel - that the Eiffel Bridge had deteriorated over the course of a few years (approximately 14 years).

It is not our purpose, however, to abandon what has been done; On the contrary, we intend to complete the work to the Zhaurin River, some 18 kilometers from Chimbo and leave it as a branch line. To this end, we will build a new bridge over the Chimbo River, since the one that exists, abandoned as it has been for so long, is deteriorated and unsafe for train traffic.

I have not wanted to accept the previous possibility, however, there are no more bridges over Chimbo to which this statement could refer.

Long after this adventurous journey, my good friend Ed Crowe, passionate about the railroad, posted this photograph of the apparent remains of the Chimbo Bridge before being scrapped two or three decades ago. According to rumors, after the bridge was dismantled, the structure ended in Riobamba. Apparently this photograph belongs to the National Photography Archive of Ecuador.

So far, the adventure of finding the lost bridge comes to an end. However, there are still some loose ends that will be the subject of further investigation. I will keep you informed.

I hope you liked this chronicle. To spice you up, I leave you with a video I made aboard one of the legendary steam locomotives that traveled the historic rails of the Ecuadorian railroad.